READ: Do you use stress to achieve?

How much stress is good for you? We all have our own particular sweet-spot with just the right amount of pressure that stimulates, motivates and inspires us to greatness. If it’s too much or too little our performance deteriorates and when it’s out of balance it harms our health.

How much stress is good for you? We all have our own particular sweet-spot with just the right amount of pressure that stimulates, motivates and inspires us to greatness. If it’s too much or too little our performance deteriorates and when it’s out of balance it harms our health.

Over the last few months I’ve been running a number of workshops on developing resilience – the ability to manage the stresses of work and flourish in a high pressure environment. It was interesting to research and select a number of exercises and themes that would help very busy managers identify and manage their own responses to the pressures of their work.

Our resilience to pressure is dependent on a number of factors, like our level of experience or skill in a particular context, what else is going on in our personal lives, the quality of the relationships and support we have with significant others, or the state of our health. But the key to being resilient is recognising when the pressure is creating stress, and then having the capability and skill to do something about it – to manage it.

The Danger of Procrastination

I was amused when I recently read an article that stated men often use the adrenalin-rush of an impending deadline to motivate them into action. It said men can, at times, wait until it’s almost too late before addressing issues or even planning for them. Without adrenalin they feel it can’t be that important so it can wait – the motivation to do something is not really there, which creates inertia. The article said that women on the other hand prefer to plan well ahead because they dislike the unnecessary pressure and prefer to avoid it by using foresight and taking appropriate action well in advance. After looking into it I discovered that this gender bias is unsubstantiated with empirical evidence so be careful, not everything that gets published is true!

However, there is a study by Tice & Baumeister (Longitudinal study of procrastination, performance, stress and health: The costs and benefits of dawdling) that researched students who procrastinated and then crammed before assignments or exams and those that planned and studied in advance. While there was lower stress amongst procrastinators at the beginning, not only did the ones who crammed get lower grades, this strategy affected their health and immune system in the longer term. They were generally more fatigued, anxious and prone to illness. There was no gender bias in this study, so the science currently shows that women and men are both equally as likely to fall into this trap. What is your tendency?

Reading the research did remind me of how much I have changed over the years. My wonderful VA (Virtual Assistant) Amanda has trained me over the last five years to be better at planning ahead. Previously when writing my article of the month I only found the motivation to put words on paper in the last couple of days of the month, and it used to cause a lot of pressure that meant other things would have to be put on hold, creating a knock-on effect. It also put unnecessary pressure on Amanda with last minute proofing and rushed preparation for publishing to my subscription list and syndication to the various blog sites.

Amanda now chases me (politely!) for the following month’s article as soon as the current one is published, on the first Tuesday of the month. This makes it far more enjoyable to write and allows more time for proofing, polishing and in the case of this irregular series on the ‘Life Paradoxes’, time to enjoy drawing the illustrations which can take a surprising amount of time because I’m still learning how to do it.

The Paradox of Poised Achievement

The balance of ‘Self-motivation’ and ‘Stress Management’ is an interesting one. On the management workshops I’ve been running, many managers say: ‘Stress is good – it gets you going’. I totally agree, but it’s about understanding your levels of stress and your ability to manage it. The problem with stress, as with much of our thinking, is that it can be difficult to identify from the inside.

When I was initially introduced to the Harrison Assessment Paradox Report I was curious about the way it measures two related positive traits that, when combined in a balanced way, produce highly effective behaviour. But when they are out of balance they produce counter-productive behaviour. Harrison’s approach is based on Enjoyment Theory and the originator’s background in mathematics, personality theory, counselling and organisational psychology has enabled him to make a rather unique contribution to assessment methodology.

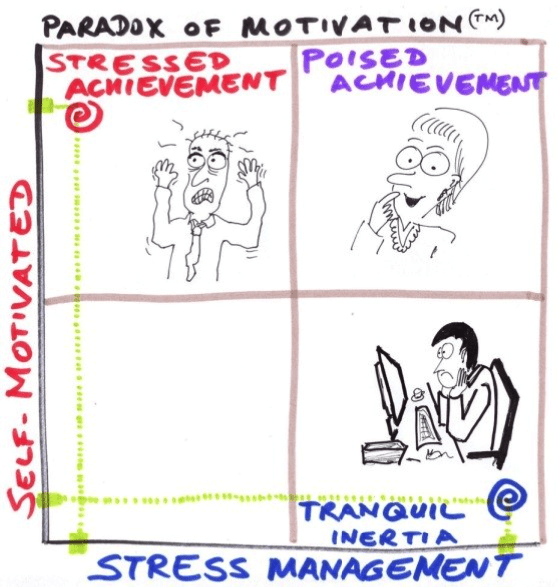

Each paradox has a ‘Dynamic’ trait and a complementary ‘Gentle’ trait. For example the traits in the ‘Motivation’ Paradox are Self-Motivation (dynamic) and Stress Management (gentle) See the illustration below.

Each paradox has a ‘Dynamic’ trait and a complementary ‘Gentle’ trait. For example the traits in the ‘Motivation’ Paradox are Self-Motivation (dynamic) and Stress Management (gentle) See the illustration below.

‘Self-Motivation’ is about the drive to achieve, including taking initiative, wanting a challenge and being enthusiastic about one’s goals. The complementary trait is ‘Stress Management’, this is the tendency to be relaxed and manage stress well when it occurs.

When we score high on both traits in a paradox we demonstrate ‘Balanced Versatility’. In this case it gives us the trait of ‘Poised Achievement’: The tendency to be highly self-motivated without becoming tense or easily stressed.

If we are highly self-motivated and don’t recognise or manage stress well, we fall into the ‘Aggressive imbalance’ of ‘Stressed Achievement’: the tendency to be very achievement-oriented whilst at the same time being tense and/or having difficulty managing stress. If not managed, this this can ultimately lead to burnout.

The opposite ‘Passive Imbalance’ gives the trait of ‘Tranquil Inertia’: the tendency to be relaxed and easy-going while at the same time lacking in self-motivation (low ‘Self-Motivated’ and high ‘Stress Management’).

If both traits are low you get the unfortunate ‘Balanced Deficiency’ trait of ‘Stressed Underachievement’: the tendency to lack achievement orientation while at the same time being tense and/or having difficulty dealing with stress.

When there is an imbalance in the traits it creates a situation where we can ‘flip’ to the opposite under pressure. So someone who has a high level of ‘Stressed Achievement’ will flip into ‘Tranquil Inertia’ when under too much pressure. This may happen at home, where we just want to chill out in front of the TV with a glass of wine, or in extreme situations at work when we end up getting distracted by Facebook or just staring at the screen. Likewise a person who has high levels of ‘Stress Management’ but low ‘Self-Motivation’ may, at times of increased pressure, get super-motivated. This can often be too little, too late at the expense of others and the quality of work. The research also shows that this approach is bad for your long-term health and well-being.

Raising Awareness

By raising your awareness of your natural preferences and tendencies you can choose to do something about it. What is your tendency? Do you notice any imbalances as described above? Would you benefit from improving your ability to manage stress when it occurs? Or do you need to get re-motivated and re-inspired with new challenges that you can be enthusiastic about?

The concept behind these Paradoxes allows us to explore the principles of the opposing traits and how we can exercise more of both. It is not about doing less of what you naturally prefer; it is about looking at any imbalances and learning ways to improve the balance between them. This can be achieved by greater self-awareness, being open to feedback and a willingness to improve. With regards to stress it is about acknowledging that it is there, labelling it, and knowing that you can do something about it.

So I invite you to explore your preferences and the preferences of your directors and managers. How well do you and the teams you are a member of, go about managing the pressure and stress of work? Are they engaged and motivated by the challenges of their job? What will you need to do in order to exercise more ‘Poised Achievement’ and have more ‘Balanced Versatility’ in your approach?

If you are interested in exploring where you and your managers stand on this Paradox and the eleven other Paradoxes in the assessment just contact at Gloria at info@talent4performance.co.uk.

Remember . . . stay curious!

David Klaasen

©David Klaasen – June 2016